The thought receptacle

Stephen's mental dustbin

Sun, 08 Dec 2019

Adventure games are disappearing (from history)

I played a lot of computer games when I was younger, and very occasionally I still do play them—old ones, I mean. Many of these games are being written out of history. I don't mean that individual games are being forgotten; of course many are, but that is inevitable. Rather, I mean that whole kinds of game are disappearing from the popular and even scholarly understanding of what games are, have been or can be. This might be what we'd expect, if we didn't have museums and exhibitions and articles and books on the subject. But we do have those things, and somehow they aren't helping. Here I am going to rant about how most of those who write or exhibit on this subject are actively hastening this forgetting, not countering it.

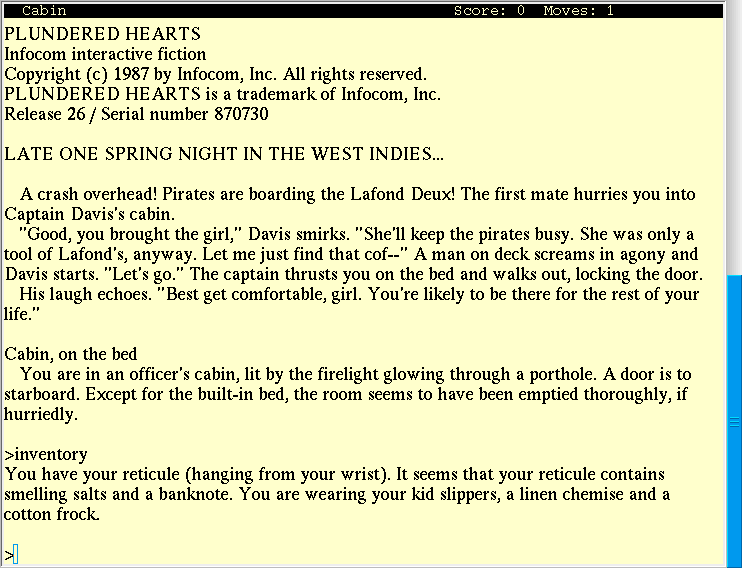

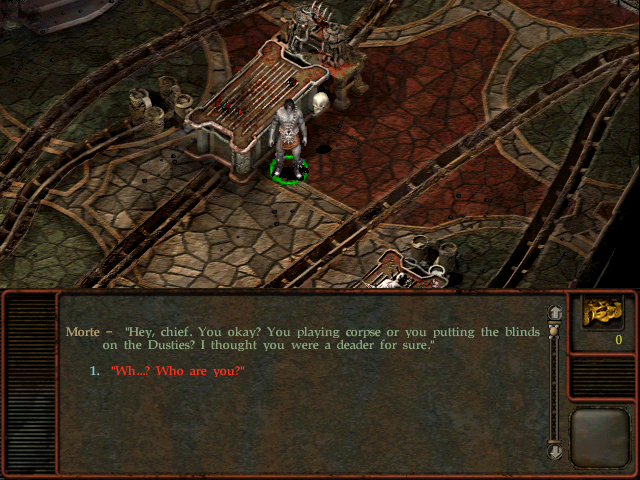

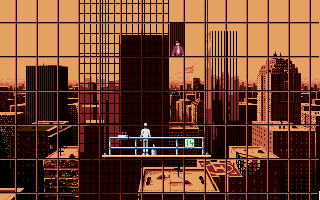

I started consciously noticing when I was reading some article or other (I've now lost the link) about Ico. It was described as an “adventure game”—always a vague phrase, but its use to describe an action-puzzle game was irksome. You may or may not share my Humpty-Dumptyish view that “adventure game” ought to mean a text or graphic adventure. The more important point is that when reading an article, watching a documentary or visiting an exhibition that purports to document some history or trend in gaming as a cultural phenomenon, it is likely that there be no mention of this kind of “adventure game” at all. Even worse, the impression given may well be that no such things have ever existed. For example, we hear endless claims that some game of the past two decades is or was “the first” to develop some aspect of storytelling or character. It almost never is, because adventure games did it first.

If this wrong pastiche of the history is repeated often enough, it will become “the truth” for most purposes. As one example, it is easy to encounter the appealing but false meme that storytelling in games is a made possible only by 21st-century technology (or current technology, or future technology). As I ranted back in 2006, I heard this coming from the mouth of none other than David Braben, clearly an amnesiac in his middle-age, who had the temerity to claim that some kind of “Hitchcock era” was imminent in gaming. (I argued that in fact the Hitchcock era had been and gone.) This social amnesia is mirrored by almost anyone nowadays who claims to be telling the story of computer gaming's history. Such a version of events is intuitively plausible: if you interpolate linearly from (say) Pong to present-day gaming, you might conclude that many modern games' far more cinematic form reflects a continuous progress in these aspects. It's just not an accurate telling of what happened, just as it would be wrong to draw a straight line between the Lumière brothers' work and the latest Marvel naffness and conclude that the story of cinema has been one of steadily more superheroes.

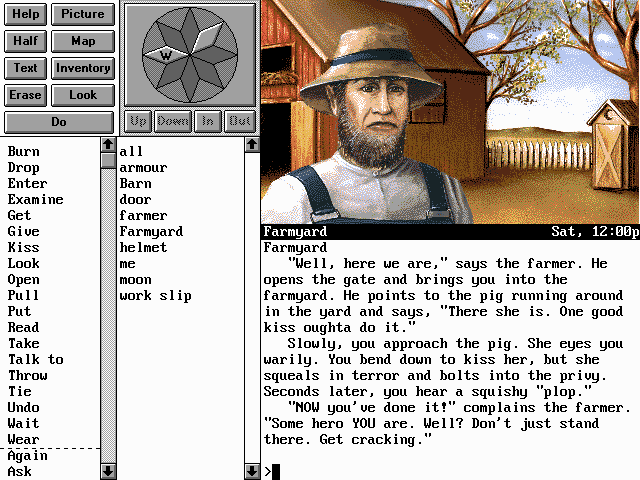

Charlie Brooker's 2014 documentary “How Video Games Changed the World” was the next culprit I encountered... or near-culprit, since it at least manages to dedicate one slot (out of twenty-five) to an single adventure, namely The Secret of Monkey Island. (You can probably find the documentary “unofficially” on YouTube, although I don't expect any single copy to hang around for very long, so you'll have to search.) Like Braben, Brooker is someone who should know better—and indeed does, I'm sure, but for some reason doesn't evidence that. We are told that Shadow of the Colossus “helped forge a new way of looking at games, one where the player could not longer be entirely certain that they were the hero”. This is hardly a new idea; it's a key theme of Ultima VI (1990) and shows up to some extent in Infidel and no doubt others I'm overlooking. A little later, listening to the documentary's gushing over The Last Of Us—a fine game I'm sure—you'd think The 7th Guest and the Tex Murphy games never happened. That's not a criticism of these newer games. I'm willing to believe that they are far deeper and more immersive than the older games I've mentioned. But it's completely wrong to say they're the first to develop these themes or ideas.

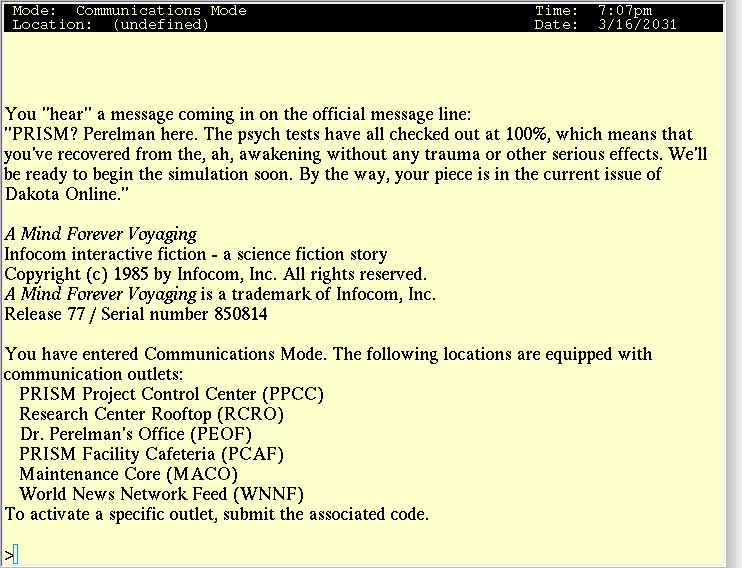

Later in the same Brooker documentary, one pundit opined that “game designers are getting older... they suddenly are thinking about games in a different way, not as systems, not as scoring mechanics, but as an emotional experience”, and goes on to claim that “in the next five to ten years we're going to see more games about emotions and about social situations, about politics and about society, because we are now living in an age where we understand what happens around us in a very interactive and very digital way”. Ever heard of A Mind Forever Voyaging? I didn't think so. And anyway, in what era was our “understanding” not “interactive”? In what way is our understanding now “digital”? The overarching pattern seems to be this: if you're called on to contribute some content about the history and trajectory of computer games, just talk some plausible-sounding bollocks. You'll pass for an expert. The prevailing standard could hardly be lower.

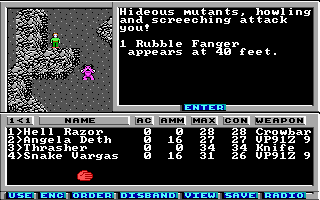

In 2015 I went to see Game On 2.0, a touring exhibition supported by the Barbican Centre (I saw it on a visit to Newcastle). It was notable for its complete lack of interactive fiction (e.g. no mention of The Colossal Cave), but also for an all-round action bias. There was also no computer role-playing game (CRPG) mentioned either, and a conspicuous lack of almost any strategy/management games (its only such exhibit was a late iteration of The Sims) or in fact any other open-ended game. The exhibition even featured an “informative” panel claiming games could be divided into three categories: firstly “thinking games”—examples including draughts and, bizarrely, CRPGs—secondly “simulation games” like sports or flight simulators—and thirdly “action games” (everything else, apparently). Of course, this is yet more bollocks. I can only assume that the exhibition's deadlines were pressing, and some hapless individual was given the task of making stuff up. (To be fair to earlier editions of the same exhibition, according to its Wikipedia article, these have included The Hitch-Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy and The Secret of Monkey Island. Presumably these were eliminated for the “2.0” version. Again, the trend is towards erasing such games from history.)

Another exhibit is an article in The Guardian from 2014. This is simply repeating the same old trope: storytelling is clearly a “new” thing in games. As with the Brooker documentary, interactive fiction is completely absent, and graphic adventures have been reduced to a single line: in an interview with Dave Grossman, The Secret of Monkey Island is described as a “black comedy” (wide of the mark). There was no attempt to reconcile this citation, of a then-25-year-old game, as a clear a counterexample to the article's main contention that only modern games have stories. One supposes that other adventure games were omitted because the writers didn't know anything about them. By writing their article, they lessen the chance that others will.

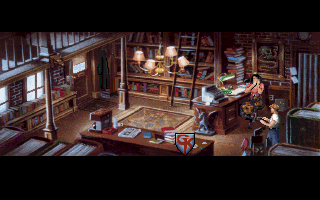

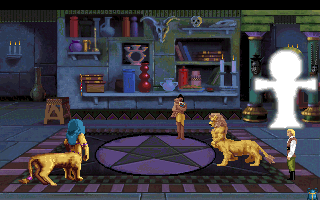

What spurred me into writing this post was yet another visit, in April last year, to an exhibition—in fact a museum—that falls into exactly the same trap: the MADE in Oakland. It's an impressive collection and deserves credit for its emphasis on playability. If you want to play old arcade or console games, it's a great place to do it. The very helpful man at the desk was quick to warn me that the museum was mostly oriented towards consoles. That was despite a rather large collection of PC big-box games dotted around in the display cabinets and shelves... most of these were not playable, and labelled “do not touch!”. (For a playable collection of computer-based games, the Centre for Computing History in dear old Cambridge is noticeably better, although still not a museum that does justice to games per se—the world is still waiting for such a thing.) So, although the MADE has its merits, again it frustrates me that it superficially purports to cover all games, and in fact more besides—it's allegedly a museum of “art and digital entertainment”. But it falls short of this description, seriously but non-obviously. To be fair, it didn't completely ignore adventure games, just very nearly: from what I can recall, the playable DOS machine had at least three adventure games. These were The Adventures of Maddog Williams, Broken Sword and Day of the Tentacle. Maybe I missed some others, but not many. Separately, you could play King's Quest—as part of the “women” exhibit. Of course if they knew as much about computer games as they knew about consoles, they'd have a lot more women to choose from: try Jane Jensen, Muriel Tramis, Lori Cole, Anita Sinclair, Amy Briggs, or many others I'm forgetting. (And if you're going to choose a Roberta Williams game, at least choose a good one, like The Colonel's Bequest!)

My theory is that these omissions are so common because they fall out naturally from an even more popular mistake: telling the story of games through the lens of hardware. Although following the progression of hardware is an “obvious” structuring device, it's also a bad one, because, predictably, it biases attention towards recognisable bits of hardware—and hence to the games that they ran. This comes at the expense of other, less recognisable platforms, even if their games were at least as important. A named machine like “NES” or “2600”is iconic, unlike the longer-lived but more nebulous home computing platforms—“the PC” but even “the Mac” or “the Amiga”. These conjure only a vague visual of mostly-beige boxes. This is compounded by uncertainty even about what counts as the platform: sometimes people identify “the PC”, sometimes “DOS”. It's no surprise these are eschewed by those looking to tell a simple story for the masses.

The Smithsonian's 2012 exhibit takes exactly this hardware-centric approach. As a result, its collection of about 180 featured games manages to include precisely two graphic adventures—namely Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders and Grim Fandango. The former pretty clearly owes its place in the exhibition to its appearance on the suitably iconic Commodore 64, and the latter because it appeared just when PC gaming had reached the mass market (also, it's deservedly revered). The period 1989–94 was pretty much the golden age of graphic adventures, but the Smithsonian's selection for those years includes not a single one; according to the story it tells, all that as happening during that time was “Bit Wars” between the Sega Mega Drive (Genesis) and the Super Nintendo. For an organisation as august as the Smithsonian, this omission is unforgivable. (No direct link, but it's fun to look for the most critically acclaimed adventure games and just how many of them appeared during that period or a couple of years either side; you can do so on MobyGames here.)

What to do about all this? Clearly the real history needs telling. Perhaps my calling out writers and curators who do a crappy or misleading job is necessary, although in a guerrilla venue like this blog, I'm sure none of them will read it. More positively, we should recognise that not absolutely everyone concerned is making these mistakes. Appearing only a couple of months earlier than the dastardly Guardian article above was another one (actually in The Observer) specifically about the indie “revival” in adventure games. It doesn't deal too much with the history, but at least acknowledges its existence—one of very few newspaper features to do so. The thoughtful writing of Naomi Alderman is also well informed, even though it rarely talks specifically about adventures. Finally, elsewhere on the web there is of course no shortage of informed content; albeit far enough off the beaten track that it won't challenge the generally accepted story.

If the technology-centric telling of history is what's causing all this trouble, perhaps we should think about these oft-neglected games completely differently. The technology is not the primary thing, in that the lineage of adventures and CRPGs lies partly in forms that exist independently of computers: traditional storytelling, riddles and geometrical or logic puzzles, board games, role-playing games (especially D&D), and (later) branching novels and gamebooks. (Gamebooks actually came later than computer-based interactive fiction, though I don't think this matters.) I'd love to see an exhibition dedicated to this wide spread of culture—including the computer-based cases where they fit, but not seeing “computer games” as a thing apart. There seems little chance; we can but hope.

I'm also hopeful that we might see books by people who really do know what they're talking about. Jimmy Maher's truly excellent Digital Antiquarian blog has already amassed enough articles to fill multiple volumes. So far, I don't know any published books on the subject that approach the same quality, although I have yet to read Twisty Little Passages. “The Art of Point-and-Click Adventures”, is fully worth the asking price for its amazing art and excellent interviews, but sadly wraps them in interstitial text that is pretty clueless. “Dungeons and Dreamers” is also an odd mixture of good and less good... its improbable storytelling style suggests that historical accuracy was not a high priority (see this hilarious Amazon review by one of Richard Garriott's school friends), and the focus on two creators (Garriott and Romero), while providing valuable depth, necessarily avoids telling a more general history.

A final question is: what about the experience? Writing and exhibitions are all very well. The MADE has a good idea in this respect: these games were meant for playing. Playing adventures, however, is hard to do in a museum; it's not as casual as action gaming. You might want to have a pen and paper to hand; you might want or need to read the manual (or experience the in-box feelies!). While it's fun to watch the intro and play the first few scenes, these games need to be preserved in a way that creates opportunity to invest time in the experience. Rather than a physical museum where people can drop in to play, it probably needs to be more like taking a book out of a library. This might be achievable in a virtual museum, curated to enable the visitor to play the game in their own home. Given the low prices on GOG, I suppose the experience they offer is somewhere close to that, insubstantial as a PDF manual may feel. However, theirs is a very limited selection, and makes no effort to present the games in historical context. GOG is rather like Netflix, when what's needed is more of a BFI-style Mediathèque.

So much for the in-depth playing experience. In fairness, not all games are worth it. Again, Jimmy Maher has the right idea: his Hall of Fame is a curated list of high-quality and/or historically important games which “respect your time and won't screw you over”—a succinct description of the sort of filtering needed. He is right to mention the fact that a large fraction of adventure games are and were awful. But so is 90% of anything. The best ones are astonishing works, and constitute a unique art form. We shouldn't allow them to disappear from history.