The thought receptacle

Stephen's mental dustbin

Mon, 05 Apr 2021

Ways to Wimpole

I was quite pleased to find that there's a nice way to cycle into Wimpole from the north-east, specifically along Wimpole Road (a bridleway) from Great Eversden. It's metalled for a decent way, then becomes a slightly stony surface over what seems like hard-packed fine gravel as it climbs up over the ridge. My tolerance to stony paths is pretty low and I found it pleasant. When you get to the top of the ridge, there is a short stretch of packed earth path to traverse along the edge of a field, but on my visit (early April, dry) this was pretty smooth and comfortable to cycle over, and you're soon joining up with the National Trust's own Wimpole Cycle Trail, again a slightly gravelly but a perfectly tolerable surface.

I must say it was lovely to cross the Wimpole Hall site with hardly any other people around... not your usual Bank Holiday. Like the cycle trail, the route through the grounds is officially only a public footpath, but one where cycling is explicitly permitted by the landowner, and the surfaces are very amenable to it.

I can back via Bassingbourn and Haslingfield, making a 36-mile round trip. For the whole ride, the opposition to East-West Rail was out in force, or at least in signage. I have some sympathy... the apparently now-chosen route makes no sense to me, and the failure to provide local stations is appalling. It seems to me that the local opposition group, Cambridge Approaches, hasn't played a good hand... they were pushing for a rather impractical and circuitous route around the north of Cambridge, parallel to the A428, and from my brief perusal I did not see a convincing story on exactly how it could be achieved. And it didn't help that their leading message was one of transparent NIMBYism, thinly disguised by the vague phrase “planning blight”. The latest “consultation” makes clear that their suggestion was not taken forward. Instead of offloading the problem onto villages to the north, they might have found their interests better served if they had argued in terms of what was best overall. The chosen route from Cambourne, cutting through the Eversdens and Haslingfield to Harston, is itself pretty circuitous and seems destined to create a bottleneck on the network between Harston and Shelford... the end result may or may not end up sympathetic to the landscape, but it seems likely to cause several years of unpleasant disruption in those villages, without the eventual benefit of a station to serve them. I am still struggling to see any reason why the old alignment could not have been adopted between Toft and near the M11 (or at least an alignment closely parallel, where telescopes get in the way), before crossing the motorway near the A10 roundabout and pushing through roughly parallel to the Addenbrooke's Link Road to reach the existing line north of the Shelford junction. That road is not very old, is much wider than a double-track railway, and was built without much fuss despite requiring compulsory purchase and demolition of several houses on Shelford Road.

Meanwhile, elsewhere on the route, the plan is to reduce the number of local stations on the Marston Vale section, and re-site those that survive so that they are further from their village centres. The claimed justification is something vague about “space” for “expansion” at those stations (what expansion?). One cynically supposes this is so that the existing station sites can be sold off for residential development, and/or for huge car parks to be built at the new ones, and/or to curtail stopping services to free up express and freight paths. I am only surmising those. But like depressingly many public infrastructure projects, despite shiny “consultation” web sites, it would be hard to imagine a plan that treats local people with greater contempt, while spending hugely more than necessary to deliver what seems likely to be an overengineered yet underperforming product.

Sun, 08 Dec 2019

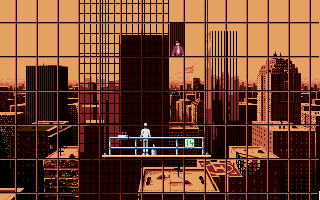

Adventure games are disappearing (from history)

I played a lot of computer games when I was younger, and very occasionally I still do play them—old ones, I mean. Many of these games are being written out of history. I don't mean that individual games are being forgotten; of course many are, but that is inevitable. Rather, I mean that whole kinds of game are disappearing from the popular and even scholarly understanding of what games are, have been or can be. This might be what we'd expect, if we didn't have museums and exhibitions and articles and books on the subject. But we do have those things, and somehow they aren't helping. Here I am going to rant about how most of those who write or exhibit on this subject are actively hastening this forgetting, not countering it.

I started consciously noticing when I was reading some article or other (I've now lost the link) about Ico. It was described as an “adventure game”—always a vague phrase, but its use to describe an action-puzzle game was irksome. You may or may not share my Humpty-Dumptyish view that “adventure game” ought to mean a text or graphic adventure. The more important point is that when reading an article, watching a documentary or visiting an exhibition that purports to document some history or trend in gaming as a cultural phenomenon, it is likely that there be no mention of this kind of “adventure game” at all. Even worse, the impression given may well be that no such things have ever existed. For example, we hear endless claims that some game of the past two decades is or was “the first” to develop some aspect of storytelling or character. It almost never is, because adventure games did it first.

If this wrong pastiche of the history is repeated often enough, it will become “the truth” for most purposes. As one example, it is easy to encounter the appealing but false meme that storytelling in games is a made possible only by 21st-century technology (or current technology, or future technology). As I ranted back in 2006, I heard this coming from the mouth of none other than David Braben, clearly an amnesiac in his middle-age, who had the temerity to claim that some kind of “Hitchcock era” was imminent in gaming. (I argued that in fact the Hitchcock era had been and gone.) This social amnesia is mirrored by almost anyone nowadays who claims to be telling the story of computer gaming's history. Such a version of events is intuitively plausible: if you interpolate linearly from (say) Pong to present-day gaming, you might conclude that many modern games' far more cinematic form reflects a continuous progress in these aspects. It's just not an accurate telling of what happened, just as it would be wrong to draw a straight line between the Lumière brothers' work and the latest Marvel naffness and conclude that the story of cinema has been one of steadily more superheroes.

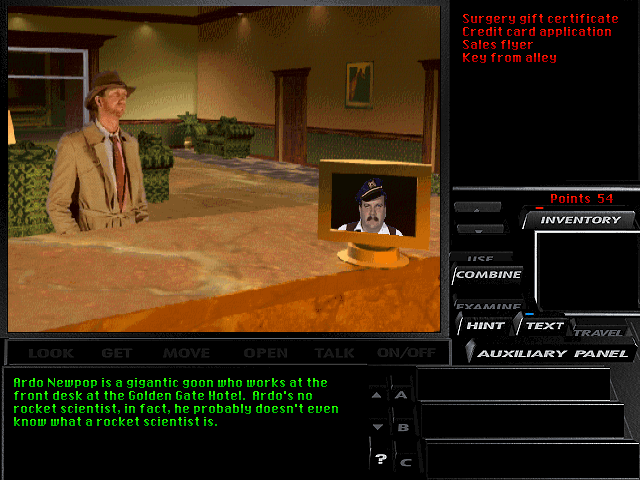

Charlie Brooker's 2014 documentary “How Video Games Changed the World” was the next culprit I encountered... or near-culprit, since it at least manages to dedicate one slot (out of twenty-five) to an single adventure, namely The Secret of Monkey Island. (You can probably find the documentary “unofficially” on YouTube, although I don't expect any single copy to hang around for very long, so you'll have to search.) Like Braben, Brooker is someone who should know better—and indeed does, I'm sure, but for some reason doesn't evidence that. We are told that Shadow of the Colossus “helped forge a new way of looking at games, one where the player could not longer be entirely certain that they were the hero”. This is hardly a new idea; it's a key theme of Ultima VI (1990) and shows up to some extent in Infidel and no doubt others I'm overlooking. A little later, listening to the documentary's gushing over The Last Of Us—a fine game I'm sure—you'd think The 7th Guest and the Tex Murphy games never happened. That's not a criticism of these newer games. I'm willing to believe that they are far deeper and more immersive than the older games I've mentioned. But it's completely wrong to say they're the first to develop these themes or ideas.

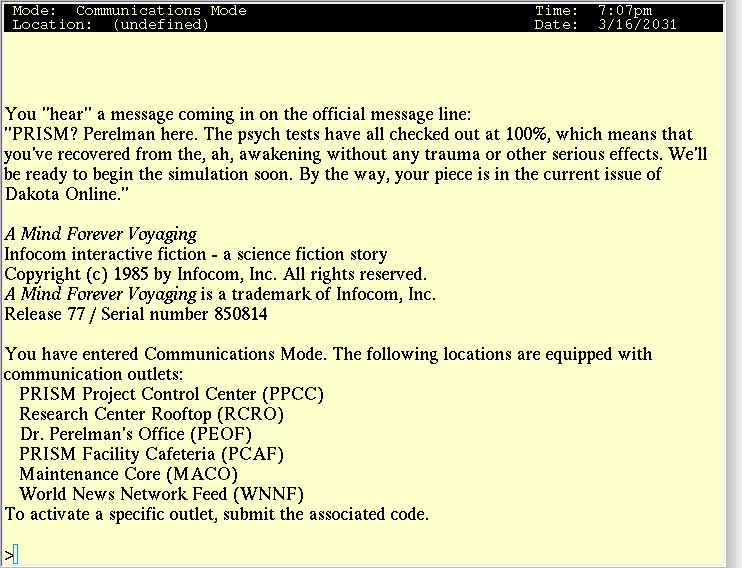

Later in the same Brooker documentary, one pundit opined that “game designers are getting older... they suddenly are thinking about games in a different way, not as systems, not as scoring mechanics, but as an emotional experience”, and goes on to claim that “in the next five to ten years we're going to see more games about emotions and about social situations, about politics and about society, because we are now living in an age where we understand what happens around us in a very interactive and very digital way”. Ever heard of A Mind Forever Voyaging? I didn't think so. And anyway, in what era was our “understanding” not “interactive”? In what way is our understanding now “digital”? The overarching pattern seems to be this: if you're called on to contribute some content about the history and trajectory of computer games, just talk some plausible-sounding bollocks. You'll pass for an expert. The prevailing standard could hardly be lower.

In 2015 I went to see Game On 2.0, a touring exhibition supported by the Barbican Centre (I saw it on a visit to Newcastle). It was notable for its complete lack of interactive fiction (e.g. no mention of The Colossal Cave), but also for an all-round action bias. There was also no computer role-playing game (CRPG) mentioned either, and a conspicuous lack of almost any strategy/management games (its only such exhibit was a late iteration of The Sims) or in fact any other open-ended game. The exhibition even featured an “informative” panel claiming games could be divided into three categories: firstly “thinking games”—examples including draughts and, bizarrely, CRPGs—secondly “simulation games” like sports or flight simulators—and thirdly “action games” (everything else, apparently). Of course, this is yet more bollocks. I can only assume that the exhibition's deadlines were pressing, and some hapless individual was given the task of making stuff up. (To be fair to earlier editions of the same exhibition, according to its Wikipedia article, these have included The Hitch-Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy and The Secret of Monkey Island. Presumably these were eliminated for the “2.0” version. Again, the trend is towards erasing such games from history.)

Another exhibit is an article in The Guardian from 2014. This is simply repeating the same old trope: storytelling is clearly a “new” thing in games. As with the Brooker documentary, interactive fiction is completely absent, and graphic adventures have been reduced to a single line: in an interview with Dave Grossman, The Secret of Monkey Island is described as a “black comedy” (wide of the mark). There was no attempt to reconcile this citation, of a then-25-year-old game, as a clear a counterexample to the article's main contention that only modern games have stories. One supposes that other adventure games were omitted because the writers didn't know anything about them. By writing their article, they lessen the chance that others will.

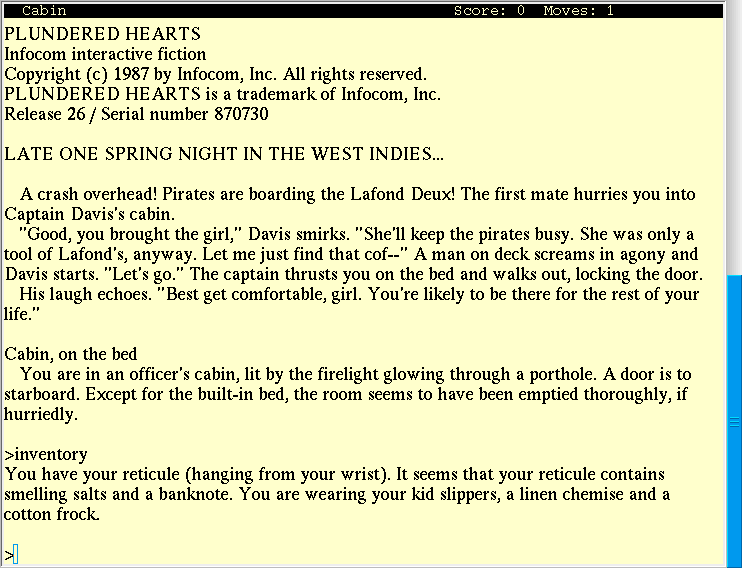

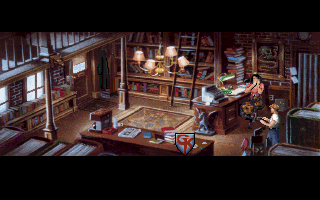

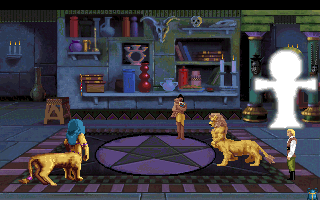

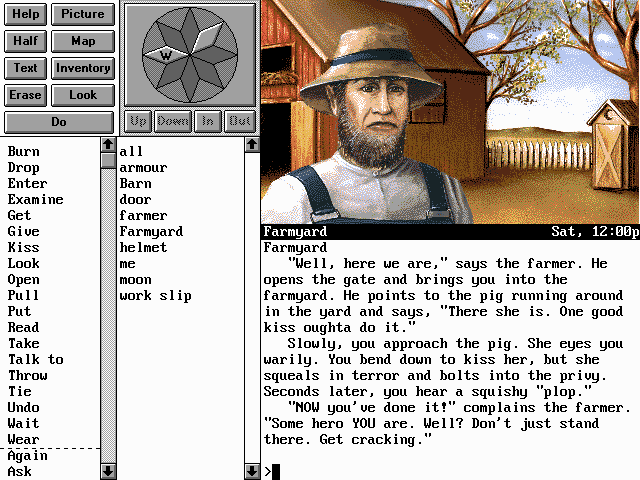

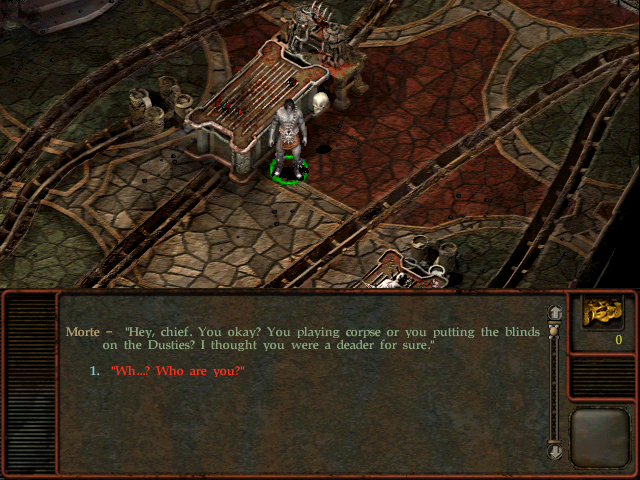

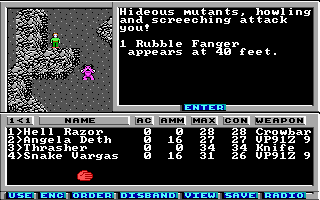

What spurred me into writing this post was yet another visit, in April last year, to an exhibition—in fact a museum—that falls into exactly the same trap: the MADE in Oakland. It's an impressive collection and deserves credit for its emphasis on playability. If you want to play old arcade or console games, it's a great place to do it. The very helpful man at the desk was quick to warn me that the museum was mostly oriented towards consoles. That was despite a rather large collection of PC big-box games dotted around in the display cabinets and shelves... most of these were not playable, and labelled “do not touch!”. (For a playable collection of computer-based games, the Centre for Computing History in dear old Cambridge is noticeably better, although still not a museum that does justice to games per se—the world is still waiting for such a thing.) So, although the MADE has its merits, again it frustrates me that it superficially purports to cover all games, and in fact more besides—it's allegedly a museum of “art and digital entertainment”. But it falls short of this description, seriously but non-obviously. To be fair, it didn't completely ignore adventure games, just very nearly: from what I can recall, the playable DOS machine had at least three adventure games. These were The Adventures of Maddog Williams, Broken Sword and Day of the Tentacle. Maybe I missed some others, but not many. Separately, you could play King's Quest—as part of the “women” exhibit. Of course if they knew as much about computer games as they knew about consoles, they'd have a lot more women to choose from: try Jane Jensen, Muriel Tramis, Lori Cole, Anita Sinclair, Amy Briggs, or many others I'm forgetting. (And if you're going to choose a Roberta Williams game, at least choose a good one, like The Colonel's Bequest!)

My theory is that these omissions are so common because they fall out naturally from an even more popular mistake: telling the story of games through the lens of hardware. Although following the progression of hardware is an “obvious” structuring device, it's also a bad one, because, predictably, it biases attention towards recognisable bits of hardware—and hence to the games that they ran. This comes at the expense of other, less recognisable platforms, even if their games were at least as important. A named machine like “NES” or “2600”is iconic, unlike the longer-lived but more nebulous home computing platforms—“the PC” but even “the Mac” or “the Amiga”. These conjure only a vague visual of mostly-beige boxes. This is compounded by uncertainty even about what counts as the platform: sometimes people identify “the PC”, sometimes “DOS”. It's no surprise these are eschewed by those looking to tell a simple story for the masses.

The Smithsonian's 2012 exhibit takes exactly this hardware-centric approach. As a result, its collection of about 180 featured games manages to include precisely two graphic adventures—namely Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders and Grim Fandango. The former pretty clearly owes its place in the exhibition to its appearance on the suitably iconic Commodore 64, and the latter because it appeared just when PC gaming had reached the mass market (also, it's deservedly revered). The period 1989–94 was pretty much the golden age of graphic adventures, but the Smithsonian's selection for those years includes not a single one; according to the story it tells, all that as happening during that time was “Bit Wars” between the Sega Mega Drive (Genesis) and the Super Nintendo. For an organisation as august as the Smithsonian, this omission is unforgivable. (No direct link, but it's fun to look for the most critically acclaimed adventure games and just how many of them appeared during that period or a couple of years either side; you can do so on MobyGames here.)

What to do about all this? Clearly the real history needs telling. Perhaps my calling out writers and curators who do a crappy or misleading job is necessary, although in a guerrilla venue like this blog, I'm sure none of them will read it. More positively, we should recognise that not absolutely everyone concerned is making these mistakes. Appearing only a couple of months earlier than the dastardly Guardian article above was another one (actually in The Observer) specifically about the indie “revival” in adventure games. It doesn't deal too much with the history, but at least acknowledges its existence—one of very few newspaper features to do so. The thoughtful writing of Naomi Alderman is also well informed, even though it rarely talks specifically about adventures. Finally, elsewhere on the web there is of course no shortage of informed content; albeit far enough off the beaten track that it won't challenge the generally accepted story.

If the technology-centric telling of history is what's causing all this trouble, perhaps we should think about these oft-neglected games completely differently. The technology is not the primary thing, in that the lineage of adventures and CRPGs lies partly in forms that exist independently of computers: traditional storytelling, riddles and geometrical or logic puzzles, board games, role-playing games (especially D&D), and (later) branching novels and gamebooks. (Gamebooks actually came later than computer-based interactive fiction, though I don't think this matters.) I'd love to see an exhibition dedicated to this wide spread of culture—including the computer-based cases where they fit, but not seeing “computer games” as a thing apart. There seems little chance; we can but hope.

I'm also hopeful that we might see books by people who really do know what they're talking about. Jimmy Maher's truly excellent Digital Antiquarian blog has already amassed enough articles to fill multiple volumes. So far, I don't know any published books on the subject that approach the same quality, although I have yet to read Twisty Little Passages. “The Art of Point-and-Click Adventures”, is fully worth the asking price for its amazing art and excellent interviews, but sadly wraps them in interstitial text that is pretty clueless. “Dungeons and Dreamers” is also an odd mixture of good and less good... its improbable storytelling style suggests that historical accuracy was not a high priority (see this hilarious Amazon review by one of Richard Garriott's school friends), and the focus on two creators (Garriott and Romero), while providing valuable depth, necessarily avoids telling a more general history.

A final question is: what about the experience? Writing and exhibitions are all very well. The MADE has a good idea in this respect: these games were meant for playing. Playing adventures, however, is hard to do in a museum; it's not as casual as action gaming. You might want to have a pen and paper to hand; you might want or need to read the manual (or experience the in-box feelies!). While it's fun to watch the intro and play the first few scenes, these games need to be preserved in a way that creates opportunity to invest time in the experience. Rather than a physical museum where people can drop in to play, it probably needs to be more like taking a book out of a library. This might be achievable in a virtual museum, curated to enable the visitor to play the game in their own home. Given the low prices on GOG, I suppose the experience they offer is somewhere close to that, insubstantial as a PDF manual may feel. However, theirs is a very limited selection, and makes no effort to present the games in historical context. GOG is rather like Netflix, when what's needed is more of a BFI-style Mediathèque.

So much for the in-depth playing experience. In fairness, not all games are worth it. Again, Jimmy Maher has the right idea: his Hall of Fame is a curated list of high-quality and/or historically important games which “respect your time and won't screw you over”—a succinct description of the sort of filtering needed. He is right to mention the fact that a large fraction of adventure games are and were awful. But so is 90% of anything. The best ones are astonishing works, and constitute a unique art form. We shouldn't allow them to disappear from history.

Sun, 12 Apr 2015

Networkopoly

[I wrote this a while back, after getting annoyed by the links to Twitter, Facebook, Flickr and other “presences” proudly sported by government services' web pages.]

The British government still does not understand the internet. They seem limited to recognising that it's an Important Thing For The Future, one that's Unfashionable Not To Use. But to them it is a foreign, other-worldly thing which they do not believe they have any role in shaping. This is unfortunate, because the internet has serious non-technical problems which are precisely the sort of thing that government power is suited to sorting out.

Imagine going back a century to a time when some new way of doing business was coming about. And imagine the government endorsing the idea that there should be only one company capable of delivering any one service using these new means. And these would not be publicly-owned companies chartered to serve the public interest. They would be private, multinational companies with no accountability to anyone but their shareholders.

This might not have happened a century ago, but it has certainly happened in the last couple of decades, with internet services. Today you can hardly find a reputable institution that doesn't proudly sport front-page links for services such as Twitter, Facebook, Flickr, LinkedIn and so on. Government services are especially keen to do this. Name a department, and chances are they'll sport such links on their front page. BIS does, of course. The DfT does. Even the NHS does. The Land Registry does. I could sit here all night visiting government organisations' web sites, and I bet I'd find few that didn't.

Any service connecting people with people is a kind of network. Metcalfe's law tells us that networks' utility increases with the square of their size. So big networks have benefits. The problem comes when private companies retain exclusive control of a large network. Like any monopoly, this is bad for competition: the incumbents have both the power (and motivation) to crush young upstarts, to aggressively seek rent, and to avoid acting in anyone's interests but their own. Their network's size and mindshare means they get “business by default”; few people think of using anything else, and it's the best network anyway, because size trumps other issues. Once a proprietary network reaches a certain level of dominance, competitors don't stand a chance.

Our incumbent network-owners are not only being allowed to perpetuate their monopolies -- they're receiving direct government assistance in doing so. The government doesn't understand that “Twitter” isn't a technology or a concept. it's a closed service run by a profit-seeking corporation. Although there is an underlying concept, which we could call “social microblogging”, the Twitter model is only one of many ways in which such a network can operate. By changing laws and incentives, governments can change these dynamics. In fact, that's possibly the most widely agreeable, right-winger-friendly definition of what government is for. When monopolies arise by natural processes, government has at best flimsy excuses. When government is helping monopolies on their way, it's clear that something has gone very wrong.

Let's consider the equivalent scenario with the humble telephone. We all know monopolies are bad, so let's skip to British Telecom at the moment of privatisation. Imagine the government allowed BT to render its network usable only by other BT customers. Although consumers are allowed to get a non-BT phone, hence “competition”, there's a catch. Don't expect to ring anyone else with your non-BT phone. You'll only be able to ring those who are customers of your chosen company. This would be unthinkable... it would be missing the whole point of privatisation. How could we expect consumers to break the stranglehold of a monopoly if choosing a different provider meant being cut off?

Networks are quite a general concept. It's clear that Twitter and Facebook are networks. But a lot of other services behave like networks. For example, eBay is a network. Why would I search on another auction site? It might offer a better experience, but it won't have as many listings, so it's not worth my while. Amazon is something of a network too, since it is a de-facto rendezvous point between people and products: linking to a product's Amazon page, its de-facto “web presence”, is how people exchange links to books, music and so on, and the page is also a nexus for reviews and crowdsourced product information. Since Amazon is the dominant incumbent in the book-selling industry, this dominance automatically disadvantages competition and rewards centralisation of content onto the Amazon network.

Google -- the last competitive triumph of public-facing internet services -- is an interesting non-example. Its search engine could compete with Alta Vista precisely because web search is not a network-like service. It didn't matter how many people were using Alta Vista already -- Google did it better. Slowly, the word spread. People didn't need to wait for their friends to switch to Google -- they just did it.

Once a service is a sufficiently large network, it acquires anticompetitive properties which only regulation can counteract. The answer is to legally enforce the openness of networks. Once a network reaches a certain size, it must be forced, by law, to operate on an open-access basis using open protocols. (Telephone networks and the rail network already have this requirement.) To this, we have to add the usual provision: the right of innovators to a limited right of exploitation of whatever innovation they create. So new network services can be rolled out proprietarily -- but once these services themselves reach a certain high level of uptake, they must be deemed mature and then subject to the same openness rules.

Before you lambast me for being all socialist in advocating “yet more regulation”, remember that competition is what I'm seeking here. Few people would claim that we have a working market in any networked sector of business on the internet. Government seems to think that the internet is “special”, that creating dependence on these private companies' networked services is some kind of brave new world of business and prosperity. It's time government learned that there's nothing that makes Internet monopolies magically beneficial in ways that other ones aren't. By supporting them, it's giving us all the disadvantages of monopolies without the benevolent intentions of state ownership. Even Thatcher would be appalled.

Sat, 06 Sep 2014

Sandy story

In November 2002, I was in Parrot Records on King Street, in Cambridge. Exhaustively browsing the record stacks, as was my newfound wont, I stumbled on a CD whose cover bore a dated-looking black-and-white photograph of a young woman holding a whisky glass, eyes downcast, looking inconsolably sad. This was Sandy Denny, and the CD was Island's 1999 compilation “Listen, Listen: An Introduction to Sandy Denny”.

At that point, I knew only a few things about Sandy Denny. One was that she had been a member of Fairport Convention for a time, including the time of John Peel's favourite line-up. Peel had offered this opinion when playing a couple of tracks from the Free Read label's “Fairport unConventional” rarities compilation when it came out earlier that year. One of these, a session version of Tam Lin, had particularly captivated me. (Currently, you can listen to the album version here, dubious legality notwithstanding.) The other thing I knew was that in an article I read about the Delgados—a favourite band of mine at the time—the author had likened Emma Pollock and Alun Woodward's vocal partnership to Sandy Denny and Ian Matthews in a the immediately preceding Fairport line-up.

In hindsight, these two facts can be generalised a little to reveal quite a lot about Sandy Denny. Firstly, she made some music which is remembered fondly by most people who knew it. Secondly, she's a cult figure of the kind to which journalists will make a knowing nod whenever they want to appear knowledgeable. Even before I happened upon that CD in Parrot, these had conspired to create a place for Sandy on my mental list of artists to investigate. “An Introduction” was exactly what I wanted, so from that moment it was inevitable that I would buy the CD, even suppressing my nascent dislike for compilations.

I didn't buy it right then, though. The price was a little high (£11.99—which was a lot of money in those days) for my meagre student budget. It also seemed premature: I should probably listen to Fairport Convention first, I reasoned. During Lent term I bought a few Fairport records and enjoyed them a lot. Some time in Easter term I bought the compilation. (If memory serves, I got it by mail order from Action Records—it was listed on their web site, but the process for getting it actually involved writing down on paper what you wanted, and posting it to them together with a cheque. Yes, children.)

I listened to it literally once or twice before the vacation, and remember being distinctly disappointed. Something about it was extremely uneasy on the ear. The five songs from “The North Star Grassman and the Ravens”, which began the compilation, were particularly difficult. They move with obstinate awkwardness, shifting from one morose harmony to another and never gratifying the listener with an easy cadence (never mind a cathartic breakdown... I could go on). They sound like a listing ship caught in heavy piano-seas during a sleet-storm in November. It was a long way from the easy melancholia I had been so shallowly hoping for.

Later in the summer, I picked up the record again, and started to get something from it. Partly it was that I finally persevered, attention unwavering, right to the end, which has one solid gold pop song (“I'm a Dreamer”) and various rather different-sounding things (not least “All Our Days”) to lighten the gloom of the opening. Partly it was that I got used to the uneasy, shifting sounds of those earlier tracks. (I'd later learn that the opening selections were an unfortunate distillation of the gloomiest parts of the album they were taken from—and that's why you should never trust compilations, kids.) Partly, also, I was carried along by the wanting to find what I felt I'd been promised in her music. I can remember walking to work one summer morning with the lyrics of “No More Sad Refrains” going through my head, and having as much of an epiphany as it's possible to have at 9.05am in Irlam—as though I'd unlocked some meaning from them, a deep truth about Sandy's life as an Unhappy Person, and the kind of personal, personable connection which is one of the appeals of singer-songwriter music, at least to little old me.

There is a knack to appreciating Sandy Denny's music, and it has to do with taking its weaknesses the right way. Once you recognise that it's not uniformly great, it becomes a lot more enjoyable. The media talk it up not because of its world-beating supremacy, but because it has great moments, historical relevance, and a cultural cachet that comes from being well-loved in spite of various flaws. Sandy's story is very much one of an underachiever, someone who struggled, and who never really capitalised on her talents. (My reading of “No More Sad Refrains” is that it articulates this very fact, in a clever and subtle way—the intentionally disbelievable resolution to leave one's “old” self behind.)

Over the following year or so, I picked up various other Sandy Denny records, including her four solo albums. These weren't easy to find on CD, which was my format of choice in those days. The later two had only been released briefly on Hannibal in the mid-1990s, and were then long out of print. With patience, I got lucky with “Like An Old-Fashioned Waltz”, eventually finding a copy going for £6 plus postage, which wasn't bad considering that one Amazon seller was asking £100 at the time. “Rendezvous” was slightly more plentiful on US import for some reason, so I coughed up 15 quid or so. Not long afterwards, there was the reissue of the Fotheringay record (a mostly-Denny project from 1970), then the Fledgling boxed set in 2004. After devouring all these, I'd sampled Sandy's work quite extensively. As is the way of these things, while I never stopped listening to Sandy's records once in a while, nor Fairport's, my focus moved on to other things.

However, it turned out that the Fotheringay reissue and Fledgling box were only the beginning of something of a revival. Island reissued all four solo albums in 2005, and a steady stream of additional reissues and compilations appeared over the following few years. This included a revamped compilation of BBC sessions, to replace the Strange Fruit “release” which had been withdrawn on its day of its Kafkaesque “release” (which hadn't preventing me from obsessively searching, eventually picking up not one but two copies, but both of which turning out to be fakes). An impressive 19-disc boxed set on Universal appeared to be the final word, appearing in 2010 and swiftly going out of print. (Don't you just love “limited edition” releases? A copy can still be yours for a mere £600.)

In recent years, someone with a lot of commercial savvy has got behind her back catalogue. Not so many years ago I was eager to lap up any and all material, so it's churlish of me (what else?) to complain. But I can't help feeling that it's all being milked a bit too cynically. I'm unsettled by the anonymous commercial fingers which type behind “Sandy's” new Facebook page, magically appearing to send me advertisements once in a while after I innocently listed her name in my musical artists (before “Like” was even a feature, kids). And I'm both impressed and perturbed by the slick “official” web page that now advertises all these various wares.

Sandy is very marketable—a tragic figure, a charismatic personality, somehow hiding her self-destructiveness and fragility behind a quick smile and looks that are at once both striking and girl-next-door. And that is not to mention the astonishing talent of her voice. It all makes so much commercial sense. The English baby-boomer generation that witnessed her first time around is now at an age where it has a lot of spare time and money. Tempering my cynicism slightly, I'm sure there is not only money, but also love, behind this revival effort. Besides, it has enabled a lot of recordings that really deserve to be on sale to be cleaned up and re-released. (My Hannibal CD of “Like and Old-Fashioned Waltz” is the worst-mastered CD I've ever heard. It sounds like it's playing from the inside of a vacuum cleaner.)

But... to truly be a treasure, don't you have to be just a little bit obscure? People gushing tributes on “Sandy's” Facebook wall sometimes complain that she never had a hit single, bemoan that she never became a “major force” (or, heaven forbid, “more like Joni Mitchell”). To my mind, these people's viewpoint is completely wrong. Sandy could and (perhaps should) have been around longer and treated us to more of her creations. But her music was always a mixed bag, some weak and some strong, always more dill pickle than cheese—and that's the way I like it.

Tue, 20 May 2014

Cyclin' USA

[I wrote this last summer, as you can probably tell.]

In late June I was in a piano shop in Palo Alto, California, signing a rental agreement. I ended up renting a portable digital piano. Since it was a portable, the guy was clearly thinking about letting me take it home myself instead of paying for the usually-obligatory delivery. “What kind of transport do you have?” “A bike” I replied. There was no raised eyebrow. Feeling myself at once the doubly-strange foreigner, I even made some comment about my self-perceived eccentrism, but he flatly rejected it. “No, no... round here is bike central!”.

In relative terms, he's right. In the San Francisco Bay area, there is no shortage of expressed enthusiasm for cycling. Local governments, including my local, Redwood City, are quick to state their firm commitment to cycling and other sustainable transport options. Companies too, including my own illustrious employer, are quick to include in their “mission” a “commitment” to something sustainable.

The problem is that it's all doublethink. Everyday people's lives are hopelessly locked into the car-dependent lifestyle. And neither companies nor any kind of government make any credible moves towards changing anything—after all, they are staffed by the very same kind of ordinary, locked-in people.

This doesn't sound so unusual. All the above would apply to most of the UK too. There are, however, big differences between here and the UK. Many differences are simply of extent—the same problems show up, but tend to occur here with greater severity. But there are also deeper differences in attitude.

One such deeper difference is as follows. In the UK, there is at least a token attempt, by authorities and lawmakers, to give cycling some kind of notional status as road users. Local authorities know that they have obligations towards cyclists, even if they don't execute them very well, and even if “ordinary people” don't think much about cycling. In the Bay area, it's subtly different. Cycling has (even) less status in the minds of local authority employees. reflecting its even lower status in the minds of people at large. Around Redwood Shores I couldn't legally turn left at a majority of junctions, because they use induction loops that are not calibrated to detect bicycles. At least in Britain, it is only the occasional rogue junction that has this property. Here it's at least half of all signalled junctions. Of course, the same city's web site proudly claims a commitment to making their roads accessible for all. But their deeds don't match up. My accumulated experience led me to believe that this is not just haphazard incompetence; it stems from a baked-in belief that cycling is not a thing that needs full consideration, that “people don't bike on this road”.

That's not to say that people here don't like to cycle. They do. Here's an illustration of the difference. There's plenty of cycle “tracks” or shared-use “trails” provided around here. In most cases, they are completely disconnected from the road. What they are connected to is the “parking lot”. Most cycling infrastructure is not provided so that people can get to places. Cycling is something to do at the weekend, very often “as a family”. How do you get to and from the cycle trail? You do so in your family car, of course. In Britain, there would at least be some ill-designed attempt at accommodating movement on and off the cycle route. This kind of omission is another sign of a locked-to-the-car mentality.

In fairness, you don't have to go far from Redwood Shores to find large populations that cycle for transport. Mountain View, with its Google and Facebook campuses, is a hive of cycle-commuting. San Francisco, too, sees a fair bit of cycling. But the inconvenience level of not having or using a car is cranked up that little bit more than in the UK. The psychological dependence is also cranked up. It's not that you need a car—it's that the idea that you both have and use a car is more firmly entrenched among people who don't think very much. In truth, you don't need a car, but you pay greater inconvenience and annoyance penalties for not having one, because you are fighting against the work of these people.

It is a cliché to say it, but California is a place of contradictions. It shows us what happens when self-consciously and proudly “progressive” people are situated among the decidedly non-progressive lifestyle norms of today's America. One outcome is that tokenistic measures are taken readily and trumpeted loudly—to eliminate plastic bags (though mysteriously, that doesn't seem to have happened around here), to recycle (which is done reasonably well, so long as you don't have an incompetent housemate who doesn't know how to separate). But the pervasive culture of thoughtless consumption is never far away. At Oracle, paper cups are abundantly supplied at every kitchen in every building. Naturally, they come printed with a lecture about how there is no such thing as a sustainable paper cup. So why provide them? Even worse, the uber-strict kitchen maintenance leaves no room for the cupboard of communal mugs—a feature of every other office environment I've ever known— so you have to work extra-hard to avoid using the paper ones.

Doublethink is alive and well here—thriving, in fact. Companies claim to be “committed” to encouraging the use of public transport, car-pooling, cycling, and other sustainable means. But they do very little, and their employees respond accordingly. Once, I happened to be out on Oracle Parkway (the road along which almost all HQ buildings are located) at 5pm. It was choked with traffic, moving at a crawl when it moved at all. My first thought was that these people must really hate their jobs. Why else would they jump from their desk at 5pm, only to sit in this traffic, rather than spending ten more minutes at their desk, which would inevitably translate into ten fewer minutes spent queueing outside, hence ten fewer minutes of their life wasted. Only if they really hated their jobs more than they hated sitting in traffic would they make this otherwise foolish trade. But that analysis presupposes that rational thought is at work. This sad traffic situation cannot be explained by rational agents, hard economic fact, or other refuges of the optimistic. It is a testament to the dull plasticity of human thought—the inability to act differently from “the norm”, despite whatever highly apparent justifications there might be for doing things differently. The state of cycling in the suburban Bay area is another instance of the same problem.

I was reading about Swift, a company founded by Aaron Patzer (of Mint.com fame, although some years earlier he also interned at the same peculiar little research lab in Princeton where I would later spend the summer of 2007). The article's omissions say it all. There's a means of transport that is the ideal solution to the “low-density metro”. It can cover miles in minutes, and it even runs on those super-cheap “asphalt roads” that the article trumpets. Yes—it's the bicycle. That a person can write such an article and jump straight from “asphalt” to “car” says a lot about the problem. People aren't locked in to the cars by force, but by lack of imagination—by the very normal human inclination to do only what other humans do, the “normal”, familiar thing, unthinkingly.

Tue, 29 Apr 2014

High streets

[I wrote this some time while I was living in Switzerland, probably in late 2012. I then edited it from a post-Switzerland perspective, but still didn't quite bother to post it.]

Recently, John Harris's article in the Guardian about the decline of the high street, and how perhaps to resist it, was trended into my view.

High streets are an emotive issue. People like them. I certainly do. However, I think John Harris's take is naive. It's not only big business that's working against high streets. Ordinary people are too. Resisting big business's influence on the high street by shoring up local support for independents is a losing strategy. It's better to take a step backwards and resist the underlying problems which give the same big businesses so much power—corporatism, unchallenged anticompetitive behaviour—than trying to fight the tide of consumer behaviour.

High streets are aesthetically appealing. They also foster individuality. Lots of small shops, run by diverse individuals, make for a heterogeneous collection, statistically highly likely to include its share of gems. Thriving high streets have character. Unfortunately, high streets are disadvantaged in two unavoidable ways: economically and transport-wise. Small shops will always be more expensive to run than a huge megastore. High streets are also (by my definition, at least) always centrally located, usually in the historic centre of a town. This sets up a classic problem: given the aspiration to keep road traffic out of town centres—a good one, I believe—people who might want to visit high street shops can't get there in their cars.

The comments on the Guardian article are interesting. They are remarkably pro-market for Guardian readership. They are also very pro-car. Of course, the ones claiming that the solution is simply to provide unlimited town-centre parking are also blinkered idiots, but I will return to that later.

What is a town centre anyway? Or rather, what should it be? I'd say it should be a pedestrian-friendly centre of work, culture and nightlife. It tends to be centre of public transportation. Should it also be a centre of shopping? Carrying shopping is one of the more defensible uses for a car, unlike travelling to work or for a night out. So, if town centres are to lose one of the aforementioned functions, I'd say shopping is one of the best ones to lose. I'm also reminded of the traffic queues that form in Cambridge every Saturday and Sunday... hundreds of people sat in their cars crawling towards the city centre car parks so that they can go to John Lewis et al. It was (and no doubt still is) a blight on the city. The cars literally blocked the way across town ... I would often want to cycle out west on weekday afternoons, and there was no route I could take that avoided the queues—which, of course, helpfully staggered themselves all over the width of the road, just to make cyclists' passage needlessly difficult. Even if you weren't trying to get somewhere by bike or car, they were still noisy, ugly and polluting.

So, would moving John Lewis (for example) to an out-of-town destination be the best solution? I don't believe so, although given the blight and timewastage of those traffic queues, it might be an improvement on the status quo. To reach any better alternative, we have to change the way shops work. It'd be nice if all those shoppers could come in by bike or public transport, experience a comfortable pedestrian-friendly high street environment, and peruse large and small shops alike. But then they wouldn't be able to take their bulky shopping home in their cars! Clearly, we need a new model of distribution: shop in-store, deliver to home.

Economies of scale make home delivery cheaper the more people use it. Given how many people seem to be driving in every Saturday/Sunday, there will be enough buying customers in any given residential locality for large stores to amortise delivery costs substantially. Of course, this is a more expensive model than pure mail-order operations like Amazon, because although you get delivery-side economies, you don't get the economies of scale of big distribution centres. But since shops need to be supplied anyway, to provide a browsing environment, the extra overhead is not that great—the same facilities that receive stock also have to be able to dispatch it, working like mini distribution centres. No doubt all this would push up costs a little, but not unaffordably.

Of course, implementing this is very hard, because it requires an investment of belief on the part of both consumers and shops. Neither one will change its ways without the other doing likewise, so it seems doomed to a chicken-and-egg stalemate. The best we can hope for is that some niche retailer pioneers the model and somehow breaks through into the public consciousness. John Lewis might be a good (okay, not-so-niche) option for that, because they already offer delivery. If they could only somehow discount delivery for people who don't use the car park, they might set about establishing the right patterns.

John Harris does make at least one reasonable point. Amazon et al get an unfairly good deal thanks to tax loopholes, and I'm all in favour of closing those. It some progress is happening on that front.

Several commenters make another good point. Independent shops are a heterogeneous bunch, and that includes their quality. Part of the value of chain stores—and it is value, much as it pains me—is their predictability. If you know you like the coffee from chain store X, you have a safe bet whichever town you're in. Having a common underlying organisation operating a large number of shops prevents those shops from repeating mistakes, so allows them to reach a given quality level faster. Of course, it also stifles innovation beyond that point, so can limit quality too. But chains often do compete in quality as well as price.

On that note, here's a peculiar anecdote to finish with: it's my impression, based on limited experience, that standards in independent shops seem significantly better in the US—despite its being home of the mega-mall and all sorts of gigantic chains. Is my impression accurate? I'm basing my experience on coffee shops, food outlets generally, and record shops. And in fairness, my experience mostly originates in big cities. Still, I'm scratching my head for the explanation.

As an aside, I first want to address another fallacy appearing there: “it's better on the Continent”. This is an appealing falsehood. As someone who recently spent a year living in a well-regarded part of the Continent (namely Lugano, Switzerland), I've become aware of the peculiar British tendency to mythologise the continent. There are good and bad examples of town centres wherever you go. In Lugano, there are markedly fewer independent shops than in equivalently-sized settlements in Britain. Satellite settlements have even less to offer. I lived in a place called Gentilino, of about 1500 people, a 2.5km walk from the historic centre of Lugano. The nearest shop selling any sort of food, except for a petrol station, is a 1.6km walk away from the village centre (and at a large difference in altitude). Other smaller settlements are very often similarly bereft. In general, this area of Switzerland has relatively little character in terms of independent establishments. This may or may not be representative of continental Europe as a whole, but we have no data to say one way or the oher. We can do without inventing a fictional Utopian “Continent”.

Sun, 13 Apr 2014

The long, long road

Last Sunday I went for short ride. I chose my route out of town to go via Long Road, after being advised that some new cycle lanes had recently been completed, with an apparently high-quality smooth surface.

The “facilities” and “infrastructure” I found were a case study in how not to do it. I took some photos (actually later the same day; forgive the blurriness). Allow me to catalogue what's wrong with it all.

Am I really supposed to cycle on that pavement? It's a pavement, with a surface barely fit for walking on—never mind cycling. Some bright spark council worker had a great idea: slap a blue sign on it, and that's the cycling box ticked. Absolutely nobody wants this.

Dropped kerbs that are not really dropped I didn't get an appropriate photo for this one. Getting on and off “facilities” is something their designers rarely consider. Getting on and off is also the part that is most easily made dangerous, and the designers rarely miss an opportunity to do so. The current thinking among those who build this “infrastructure” is that a narrow section of partially-dropped kerb, like you get on pavements in front of driveways, is good enough for bikes too. This is another (slightly different) case of repurposing existing pavement designs for bikes, and is completely inadequate. We need kerbs that are dropped right down to road level.

Now we are three A little further east along Long Road, we now have three distinct tracks or lanes, not counting the carriageway, on which cycling is somehow sanctioned. On the far left, only just visible, is the shared-use pavement (photo above). A new cycle-only lane spins off in the middle (soon to reach a bizarre lay-by area that I've yet to understand the function of), and there is also an on-road lane. All this suggests that there is no shortage of intention, or funds, for catering to cycling—what is lacking is thought-out design and general competence. I would never consider using anything other than the on-road lane (or the carriageway) here.

That pavement looks a bit better, but am I supposed to cycle on it? In the middle distance, we can see the pavement has been renewed. Is this one of those pavements that I'm supposed to cyle on? It's hard to tell, because there are no signs except a single very tiny blue shared-use sign, which you can see as a tiny smudge of blue in the above photograph—if you can find it at all. It is far too small and appears far too late to be a useful cue to get off the carriageway (even if there were some properly dropped kerbs about, which there aren't). It's also not clear that this sign isn't referring just to the side-path on the left, that leads to the guided busway.

That's the west-to-east direction. On my first run past here, I just kept going east along the carriageway and went about my business. But when I came back to take the photos, I U-turned here and inspected the “facilities” offered to the westbound cyclist. I started by assuming I had got there on the nice new smooth surfaces which apparently are (despite lack of signage) shared-use paths.

Oh, now I'm being led back onto the carriageway. I'd better do so, because the pavement that follows is clearly a no-cycling one.

...but it isn't. We find out at the next junction, where Toucan crossings guide us from pavement to pavement, handily interrupted by a completely unnecessary traffic island. Aside from the fact that we were just shepherded back onto the carriageway, meaning you need magical powers to realise that you could take these Toucan crossings instead, doing so would be tedious at best. It involves at least four of those non-dropped kerbs, stoppping and getting down from the saddle to press those pedestrian-height buttons, one or two lengthy waits for the crossings to change, and (at other times of day) evading with pedestrians on the pavements.

Pull 'em out, then shove 'em back in Now that we've been guided back onto the carriageway, let's assume we followed this guidance (even though, as I just noted, it turns out this was optional). The road narrows severely, and just as it begins to do so, there's a handy bike painted on the carriageway, as far left as possible. This is there to tell cyclists where they need to be to maximise the danger. The only way to safely navigate a severe narrowing like this is to take the lane, not to hug the kerb. So, the road markings are there to encourage cyclists not to do this; it exists to ensure that cyclists will be cut up (or worse) at this spot on a regular basis.

Another one: the next attempt at merging cycles back onto the carriageway has a lot in common with the previous one: it injects bikes at an angle that is sure to create conflict, with no clear indication of who should give way to whom.

I really hope that pavement isn't for cycling on Beyond the above photo, the pavement returns to its old, narrow bumpy self much like in the first photo. After the previous photo, you'd hope that that's not a pavement that anybody is expected to cycle on... but it is. As I cycled past I could vaguely make out the worn remains of painted bikes on the surface. They even painted some helpful give-way triangles at the various driveways and side roads that the pavement intersects. I didn't take a photo of that bit, but I have a bonus photo that I took on Trumpington Road immediately before all of the above.

Cycle gutter The view above is from Trumpington road's southbound “bus, taxi and cycle” lane. Within it is painted what I'd hope is the most insultingly narrow cycle lane you've ever seen, except that it's possible to find even narrower ones. Whenever I go down here, I deliberately cycle outside this lane (but inside the wider lane). Soul-crushingly, they recently re-painted the lines on this section of road, and, you guessed it, repainted the same stupidly narrow gutter marking, oblivious to its sheer inutility.

“Dismount and use footway”, even though there's a perfectly good carriageway. There are some works on Trumpington Road right now, so a section of the bus-taxi-cycle lane is closed. Helpfully, they have one of those nice red signs, and it says “cyclists dismount and use footway”. But the main carriageway is still open. So I just used that. Whose idea was the sign, and what purpose does it serve except to many non- cyclists believe that cycles have no right to use the carriageway?

That's the end of the photos. But even if it weren't for Long Road, the rest of my ride that day was also full of case study material—quite impressively so, in fact. I counted 22 different stupidities on my ride. Many miles of my ride were gloriously facilities-free, on quiet country roads, so the “facilities” were incredibly densely clustered. Sadly, most of them were relatively newly built. I'll save a run-down for a follow-up post. For this one, a quick summary would be as follows. I hate cycling on pavements. I hate doing so, and I hate being expected to do so. It's not okay.

Thu, 10 Apr 2014

The joy of discovery

[I seem to have written this in June 2010. I joined up a few half-formed sentences, but otherwise it didn't need much finishing off.]

The most joyful times in life are often times of discovery. Discovering people, music, art, places, food, drink and pastimes can all be among the most exciting and rewarding things life has to offer.

My life in Cambridge (I could just say “my adult life”) has introduced me to many of the discoveries that have brought me the most joy. My interests or enthusiasms for music, film, wine, cycling and other people's company have all essentially arisen or properly sprung during my time here. I've also discovered some truly wonderful people and the pleasures of spending time with them. Summer evenings with friends, a walk at dusk or a new and perfect sandwich were all essentially unknown before I came to live here.

However, recently I've been forced to confront the fact that I just haven't been doing that much discovering lately, and that my life has been correspondingly low on joy. I don't want to overstate it; I've always had one thing or another going on that has kept my faith somewhat alive. In the last couple of years these things have included the radio of Gideon Coe, the joys of Belgian beer, cycling adventure, and the odd special person I've been fortunate enough to get to know.

What is joy anyway? It has something to do with an involuntary urge to smile. A friend once claimed I was a joyful person, which surprised me because often I feel anything but. Still, I must admit I am prone to sudden bouts of joy. I can be eating breakfast or generally daydreaming when the thought of something catches me and cracks me up completely. My joy-o-meter registers how often this happens, and this post is lamenting that it seemed to happen a bit more when I was younger.

Part of the secret seems to be to keep up the energy of exploration: move, don't stand still. Keep on digging for the good stuff, keep on challenging yourself, and don't stay in the same place for too long. Unfortunately I'm also a bit of a sentimentalist: I look back fondly at joys past and feel unable to part from them, even though the discovery was long ago and the joy now only a memory. It's a difficult idea to swallow: that life springs from freshness, that standing still means staleness and decay, and that today's bright fountain of joy is tomorrow's sentimental baggage.

Childhood is a process of continual discovery, which is why I think most people look back on it so fondly. I'd be quick to add that its joyfulness is often balanced by a lot of pain and confusion, and shouldn't be romanticised, but I suppose every one is different. What seems not to vary is that as we progress through adulthood, it gets more and more difficult to keep up the discovery rate. Jobs and commitments tie us down in space and drain the energy that we might otherwise spend on our imagination. Imagination is one thing you can't afford to lack if you want to keep challenging yourself, because as you discover more of life, it takes creativity to see where the next piece of unknown joy might come from. A high-entropy diet seems essential; if you have tips on how to get your w-a-day, I'd love to hear them.

Blog holes

I haven't blogged regularly for a few years now. Even when I did, though, I had the bad habit of never posting a reasonable proportion of the articles I wrote. I'm trying to improve on both of these sorry situations. So, I'll try to post at a reasonable rate, and much of what I post will be articles I wrote some time ago. It's a bit of an experiment—I hope it proves worthwhile.

Sat, 05 Apr 2014

Something about cycling

I seem to be thinking a lot about cycling these days.Too much safety talk spoils the cycling broth

Safety is important, but we have a problem. When you ask someone why they don't cycle, safety is what they say. Let me repeat that. Safety is what they say. That doesn't mean cycling is dangerous; it means that it is perceived as dangerous by people who don't do it. Many apparently pro-cycling bodies spend a lot of energy talking about safety, campaigning for more of it, and so on. Most of them are aware that perceived safety, not actual safety, is the real issue. Then they proceed to act in ways that vastly worsen this perception. I follow various cycling sources on Twitter, and it's a depressing read, because it's always highlighting the never-ending stream of accidents. To somebody who doesn't cycle, this would surely seem terrifying. Cycling is not risk-free, but neither is walking, or driving, or taking the train. The health benefits of cycling far outweigh safety risks. The social benefits of a modal shift towards cycling (away from motoring) are also huge and unquantifiable. Even if we find ourselves with gold-standard Dutch-style facilities, we would only reduce fatalities per kilometre roughly by a factor of 2.5. This is obviously a good thing, but we need to get it in perspective. How much ill health and premature death is happening because of people being discouraged from cycling Right Now? How much social benefit are we stalling by telling people that it's not safe to cycle until we have Dutch-style roads? It's as if in the quest for proper government attention to cycling as a mode of transport, we've had to resort to shouting “cycling is dangerous! so please give money...”. This is the wrong thing to shout. Whatever scraps government might throw as a result, the current level of safety campaigning is counterproductive overall. We need to shout instead that cycling makes people happier and healthier, and makes economic sense, and that therefore we should take action to encourage it. We need to fight the false perception that cycling is a dangerous fringe activity. That means being much more focused and careful in how we present and debate the issue of safety.

Sport versus transport

A surge in popularity of cycling as a “sport” is all very well, but let's not keep mentioning it in the same breath as transport issues. Cycling to get around and cycling for sport are very different things. It's great that Britain has many Olympic cyclists, but that bears little relation to our transport habits.

Recreation versus lifestyle

Weekend cycle rides are one thing. Embracing cycling as a part of everyday life is quite another. That's why efforts such as recent bike-friendliness grants in the Peak District are a distraction from proper investment in other areas. As one commenter insightfully notes under that article, the public transport connections to and in the Peak District remain poor. So, under current conditions, the grant cannot do anything more than promote cycling as a weekend activity “for families”. That's not a bad thing, but we must be careful not to let it be portrayed as a substitute for proper investment in both public transport and support for everyday cycling—the things which together can enable and accelerate the shift away from the car. As before, we need to distinguish carefully what kind of “cycling” is being supported, and not accept any cop-outs from politicians that try to paint support for one kind of cycling as support for other kinds.

Facilities of the month

The blithe call for “facilities” often accompanies the safety message. This is always a dangerous call, because as we know, many attempts at facilities are of negative overall value. A large fraction are simply dangerous, owing to flawed design or substandard implementation. Other facilities might suit some set of people but can easily disadvantage others, either directly or (more likely) indirectly—such as by encouraging dangerous or disrespectful driving around those who choose to avoid them and cycle on the road. Aside from our local authorities' great track records of producing really badly designed attempts at facilities, I'm concerned that we're not emphasising a specific and subtle point: the population of people who cycle contains more disparate needs than users of other means of transport. This is a result of both disparate physical capabilities and disparate experience levels. While I'm all in favour of facilities which will make an underconfident person feel secure, they might not be the same facilities that make cycling quick and convenient for an experienced rider (which we all become, if we cycle enough). Provision of “facilities”, however inadequate or dangerous, is perceived by many [drivers] as eroding the right to cycle on the road. We must fight this attitude. (Of course, most “facilities” today are narrow, twisty, badly surfaced, constantly yielding to side roads, and full of pedestrians—in other words not “safe” for anyone. We must fight those too.)

No more “cyclists”

Talking about “cyclists” is something I've started trying to avoid. It somehow suggests that people who cycle are a separate species, thereby perpetuating the in-versus-out group mentalities that plague popular attitudes to cycling. I prefer to say “people on bikes”. I think if everyone did this, it might help somewhat to combat “species prejudice” that humans are unfortunately prone to.

Cycling, and walking, but not ‘cycling and walking’

“Action for Roads”, a government report published last year, contains 15 mentions of the word “cycling”, but 10 of are in the phrase “cycling and walking” (or something very similar). Anyone who's cycled beyond a few teetering first steps will know that cycling radically different from walking and needs wholly different kinds of provision. We need to fix the mistaken belief that the two can be lumped together. A recent ride reminded me that even Sustrans—an allegedly pro-cycling charity— offers routes with an appallingly high frequency of shared-use sections, many of which are simply a relabelled pavement—narrow, badly-surfaced, highly unsuitable for cycling, and causing unpleasant conflict with people on foot. This is worse than a waste of money: it's spending money on making things outright worse.

It's the culture, stupid

David Hembrow has an impressively complete selection of compelling arguments about why high-quality Dutch-style facilities are not only a good idea, but completely achievable in Britain, and why the counterarguments wheeled out by naysayers are all flawed. But one thing that's very hard to counter is the fact that in the Netherlands, practically every driver also cycles. The Dutch never lost their cycling culture. Ours was thoroughly lost many years ago, and this makes it an uphill struggle in Britain.

Where to begin?

I recently joined the Cambridge Cycling Campaign, and the membership form asked me the following questions. “What do you think most needs to be done to help cyclists? Is there anything you particularly think the Campaign should be doing?” I found it surprisingly hard to answer! I also want to nitpick that helping those who are (currently) non- cyclists should be part of the agenda too. Anyway, eventually I wrote the following. “Proper consideration of cycling in town planning, road design, new development regulations, etc.. Responding to popular misconceptions about cycling as they appear in journalism, policy statements, etc..” There is so much said and written about cycling that is either misleading or outright wrong. I believe that all this misinformation chips away at the popular perception of cycling, and we must fight it continuously. It appears to be a neverending struggle, but also, some strange small amount of momentum seems to be building here in the south-eastern UK in the last few years. We need to keep on pushing.

Wed, 11 Sep 2013

The US Open—a report from your man in Flushing

With the end of the US Open yesterday, it seems past time that I post the results of my fact-finding trip to this intriguing tournament, which I carried out a little under two weeks ago. Being well-versed in lawn tennis as played in Britain, and expecting no less of my readers, I will simply highlight the few important differences which distinguish the sport on this side of the Atlantic.

The grass is blue, and incredibly short—so much so that it is very nearly impossible to see. Of course, the brilliant blue hue of the courts reminds us that it is there. Blue grass is a popular variety native to certain parts of North America, having been cross-bred in Appalachian areas from British and Irish strains. (Of course, it also gives its name to the music which also flourished in these areas. As I will report shortly, in America the worlds of tennis and music have more than just the colour of their grass in common.)

Tournament colours are blue and white, with occasional red—a welcome nod to the British and French origins of the sport of tennis. However, the towels provided for the players exhibit an intriguing secondary colour scheme: of white on white with white text on a white background. In contrast to the overpriced souvenir towels of Wimbledon, this colour scheme decision reflects an admirable audience-minded, do-it-yourself spirit. To make your own US Open souvenir towel, one can do do as follows. Firstly, simply buy any plain white towel. Secondly, enjoy!

Pimm's is nowhere to be seen. At first, this absence might seem horrifying. However, it is explained by a little consideration of timezones and some simple logic. In this more westerly timezone, Pimm's o'clock occurs before the sun is past the yardarm. As such, tempting as it might be, it would simply be improper to indulge in such a drink during play at the tournament. This loss might seem hard to stomach, but as any tennis fan will know, other beverages can approximate the experience not too shabbily. As a tribute to Louis X of France, cooled wine is available at the Open from certain vendors.

Overarm throws are the technique used by ballboys-and-ballgirls to transfer balls among each other, instead of rolling balls along the ground as practised in Wimbledon. This reflects the wider North American preference for air travel over surface travel—at least since the decline, in the middle decades of the 20th century, of North American passenger rail travel and green-grass-court tennis.

Piped music is a very noticeable presence. It is one of the US's many under-recognised achievements to have developed the world's most extensive and sophisticated music plumbing infrastructure. Music is piped to practically all commercial buildings. (Another little-known fact, however, is that like the grid pattern and the underground railway, Glasgow was an early pioneer—but, in an unfortunate lack of foresight, its pipes were made with too small a diameter, making them suitable only for piped pipe music.)

Musical connections more generally play a strong part at the Open. It may surprise European readers, but here, tennis and music have often gone hand-in-racquet. One of the grandstand venues is the Louis Armstrong stadium, named in recognition of the remarkable double singles career of the great jazzman. Seeking to avoid confusion between his musical achievements and his tennis career, Armstrong played under the moniker Satchmo “Lefty” Gonzales, and won a number of minor singles titles before an unfortunate recurrence of his “trumpeter's elbow” forced him to quit the sport at the height of his powers. Decades later, Michael Jackson would immortalise tennis artist Billie Jean King in his smash-hit single. In the world of tennis she was already immortal, and indeed, the US National Tennis Center in Flushing is named after her. The depth of these musical connections are doubly humbling to us Britons ever since Tim Henman's charity single version of “The [Semi-]Final Countdown” so infamously failed to capture the nation's imagination.

Salesmanship and sponsorship are more prominently featured than at Wimbledon. Thankfully, this is done in an earthy and unpretentious manner. The street-talking salesmen of elaborate video gadgets for multi-court viewing were refreshingly familiar and will be comprehensible to anyone who has viewed The Wire. (They seemed puzzled when I inquired whether they had a “burner” version on offer.) On the court, large companies have generously donated unwanted banners in the tournament colours, along with assorted unwanted adornments which the tournament organisers playfully use to decorate the net, lending a likeable “scrapyard feel” to the ambiance.

The Line is surprising, since it does not exist. One would surely expect this fine American equivalent of that Wimbledon landmark, The Queue, but there is none to be found. In a remarkable piece of innovation, paying customers simply walk in, having already bought their tickets, since patience is not a criterion by which tickets are apportioned. Depth of pocket rules supreme. Sadly, the higher ticket prices do not seem to lessen the overpricing of “optional extras”, meaning food and drink. In fact, they seem even more inflated. Unfortunately, your correspondent was unable to purchase anything to evaluate its value-for-money more closely, having been caught unawares by the surprising finding that pounds Sterling were not acceptable currency.

Etiquette is every bit as established as at Wimbledon, but the rules are somewhat different. At the US Open, it is very poor form to clap except for a winner by your favoured player, or an error by the other player. Never clap at good play from the other player! Although this will feel counter to the sensibilities of most well-brought-up Europeans, a little reflection will reveal the equally upstanding American perspective: that to applaud for an action one finds displeasing is, above anything, dishonest. Besides this, it is also an unnecessary noise that might potentially disturb others.

That is all I have to offer you, dear readers. I hope it has been an enlightening experience, just as attending the tournament was for me. In my next report, I'll be sharing my experiences contrasting the factories of bustling Keswick with the “graphite belt” of Lakeland's new-world rival—Pennsylvania.

Wed, 19 Jun 2013

Arrivederci to all that

Since a couple of years ago there's been a new camel in town, and it's a not-writing-a-blog camel. Sorry about that. I think this camel originates in Oxford somewhere, and has been following me around, but I'm trying to get rid of him.

My year in Lugano is fast receding into the distant past. It's a hard year to summarise. Work-wise, I learnt less and gained (even) less satisfaction than in the previous year, but I have also ticked a lot more career boxes. So I have possibly made more progress towards some future satisfaction, whenever that might turn up. More personally, it feels as though the year's generally low-fun diet has further chipped away at whatever youthful exuberance I had left. But I'm hoping that it's reversible. There's not much substitute for company that makes you laugh, .

I have actually still been writing the occasional blog item—just not actually finishing or posting them. But I'm going to follow this post up immediately with one for which I even did the finishing bit, just not (until now) the posting bit.

(That reminds me: I need to write some macros to make it easier to include photos in these pages. I'm sure some of my reticence is down to the fact that my web set up makes it unnecessarily much faff to post things.)

Mon, 25 Feb 2013

Price of living

(I wrote this some time ago, which probably shows, but it still seems worth posting....)

“Cost of living” is a phrase I've heard a lot in the last year or so, both when talking to friends about their moves and when considering my own potential moves. It took me a while to realise that it's a phrase that usually doesn't mean what it appears to mean. Large cities are often cited as having “high cost of living”. But the whole reason we have cities is for economies of scale! Living close together is cheap, because infrastructure costs are so well amortised. This includes utilities, transport, food supply, and almost everything else. Living in rural areas, conversely, is expensive! That's why rural post offices struggle to keep open, rural public transport is generally poor, and so on.

What people mean when they say “cost of living” is actually “price of living”. Most large, successful cities have high prices of living because they are desirable as locations. In turn, this is largely because of their high value, including social and cultural value. Among these values is the diversity of employment opportunities that a city environment can offer. This demand is exploited by land- and property-owners, who adjust their prices far above cost. High demand combined with collusion creates a lack of choice, effectively coercing people into paying their high prices, regardless of how much lower the cost might be. Cost and price are definitely not the same thing.

There's something interesting about this adjusting-the-prices phenomenon. When traders do this by explicit collusion, it's called a cartel, or price-fixing. It's clearly scurrilous and interfering with the operation of the market. But when traders do the same thing without explicit communication, but nevertheless collectively, it's called “the market”, as in the so-called property market. The net result is the same as price-fixing, so why do we treat the two cases so differently? This might be classic supply/demand economics, but it is a very different kind of market from the good kind which most market advocates like to describe. In the best examples of markets, prices are driven by cost and kept down by competition. With property, prices are driven by demand and kept up by implicit collusion.